Few organisations have the processes in place to root out the ‘unknown knowns’. Chris Paton extols the virtues of ‘business wargames’ as a means of getting this invisible enemy into your sights

This article was written for and published by Continuity the Business Continuity Institute Magazine for their Q2 2017 issue. Read the article on the page alternatively read the full magazine.

The role of business continuity has arguably never been more important than right now. The global and national strategic landscape is changing dramatically, creating uncertainty in businesses and markets. This is driving a laser-like focus on business continuity as organisations look to bolster their resilience capabilities in response to this increasing uncertainty. But this heightened interest in resilience also raises the question of whether any system can ever be considered truly ‘invulnerable’?

Perhaps a better approach is to take a step back, to reassess what is considered the status quo and to ask yourself, “Where are my blind spots?” Blind spots are those areas which you simply aren’t looking at. You aren’t tracking the trends, thinking about the issues or preparing for the consequences. In a business continuity context, blind spots are those areas which have the greatest potential to leave your organisation exposed.

Caught off guard

In September 2008, I was an offi cer in the Royal Marines and was head of operational planning for the military and civilian efforts in Helmand Province. The aim at the time was to create a ‘protected zone’ in which Afghan Government and USAID/Department for International Development staff could deliver vital aid and support development in the region.

Everything we did in planning and preparing for our deployment revolved around us building on the status quo; establishing a protective barrier of bases around the outer areas of Helmand and sheltering the ‘safe space’ within it.

My own base, at the headquarters, sat in the very centre of the protected zone. On the fourth night of our tour of duty, before our forces were fully in place, 400 insurgents that had bypassed the outer bases began shelling us with rockets and mortars, whilst their foot soldiers launched a coordinated ground attack.

The shock and confusion this caused was considerable. My base was not full of combat troops ready to deal with such an occurrence; we were mostly senior leaders who were responsible for the co-ordination of the Helmand mission. Needless to say, during a long and challenging night, old skills were rapidly dusted off and experience came to the fore!

With hindsight, it was clear our mistake was to accept the existing model as fi t for purpose and not look for gaps in our knowledge. Some people were already aware that the outer bases did not provide a solid barrier and were concerned that focusing combat power on the outer bases left a dangerous vacuum in the ‘safe space’ – but their voices were not heard during our preparation and exercises. Whilst we developed good contingency plans, we did not challenge the validity of the model we had been given, nor ask colleagues at all levels for their views.

Challenging the status quo

In my eclectic life experience, I have often observed this type of failure. Most organisations, regardless of sector, work with what they know, and rarely step back to challenge what they believe or the model they use.

As described so well by Eric J. McNulty in his article for “Strategy + Business”1, leadership in a volatile and uncertain environment:

“calls for questions — lots of them. Penetrating questions that ferret out nuance. Challenging questions that stimulate differing views and debate. Open-ended questions that fuel imagination. Analytical questions that distinguish what you think from what you know. [This] will help you see patterns and make more accurate predictions. As a leader, you must encourage open, direct feedback as well as ideas that challenge the status quo.”

The tendency to focus on the familiar, rather than the unknown, is described with precision in “Bolt from the Blue: Navigating the world of corporate crises” by Mike Pullen and John Brodie Donald.

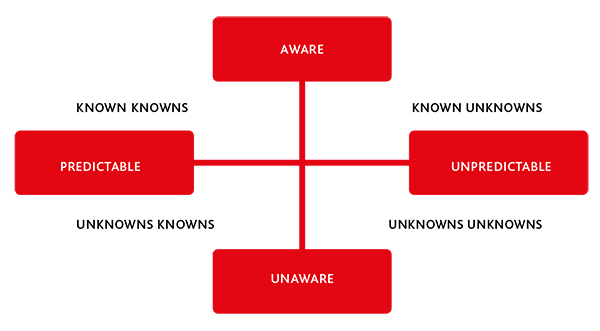

In the book, they develop the following framework:

The ‘known knowns’ are those issues that surround daily life in the organisation: cash flow, supplier agreements, marketing, salaries etc. These can be mapped out and managed, and virtually everyone across the organisation is aware of them.

The ‘known unknowns’ are the standard purview of the business continuity experts: cyber threats, fire, flood, theft, loss of electricity or loss of use of the building etc. These are issues that the organisation is aware of, has a plan for, but cannot predict with any certainty when they might happen.

The ‘unknown unknowns’ are the classic lightning bolts. Nothing can help you specifically prepare for these. Nevertheless, a crisis management plan should be designed to cover such an eventuality, because the need for response and preparedness remain, regardless of the perpetrator.

My Helmand Province experience sits in the fourth quadrant – what Pullen and Donald refer to as the ‘unknown knowns’. These are issues that some within the organisation are aware of but haven’t communicated. They are ticking time bombs which could have been predicted and included in the business continuity plan. However, whether due to the organisational culture, governance structure or casting a blind eye, they simply do not come to light until it is too late.

There are two other human factors that facilitate the emergence of blind spots. The first relates to the type of employee we look to attract into our organisation. Companies tend to employ people who ‘fit’ their employee profile, people who have very similar outlooks and interests to the existing corporate view. This, over time, means that the organisation becomes homogenous and ‘group think’ emerges.

The second relates to what I call ‘wilful blindness’, i.e. a refusal to engage with an unpalatable truth. Faced with a significant problem, organisations will often try to stick their collective heads in the sand and hope that the situation simply goes away. In his book “Black Box Thinking”, Matthew Syed describes with startling clarity the role that wilful blindness has played in some of the most damaging of institutional and corporate failures.

Going to war

So how do we create a ‘safe space’ in which organisations can challenge thinking without it damaging relationships? One tool to consider is a ‘business wargame’. This methodology, properly designed and facilitated, allows for a controlled challenge to the plan, bringing positive critique and pressure testing assumptions. It is delivered through three teams: a blue team which champions the plan, a red team which critiques it and a control team which manages the pressure in the room and records outputs.

The ‘red team’ represents all the stakeholders, both internal and external to the organisation, who could be effected by the issue1. They can be role players or ‘real’ people. This delivers a thorough challenge from a wide range of perspectives. In doing so, planners move beyond a templated fire/flood/ terrorism response and instead question the status quo.

Implementing this type of test is not straightforward. Such exercises can leave business leaders feeling anxious and exposed. There are equally difficulties for their team members, who may be uneasy at the thought of questioning senior members of the organisation. Conversely, for leaders and teams comfortable with challenge, sometimes the tests simply don’t go far enough.

The following tips can help address these problems:

- Design: The design of a wargame is as important as the event itself. Careful consideration needs to be given to identifying the right people to take part. You will need individuals prepared to contribute constructively, but also ensure that you recruit some participants from outside your organisation. This ensures you break out of the ‘group think’ cycle.

- Factual preparation: People need to come into the room with all the information likely to be needed at their fingertips. Posing a challenging question only for the response to be ‘we’ll have to go and find that out’ is inefficient; participants need to think through in advance the types of issues that will come up and ensure they have all the facts.

- Mental preparation: Participants need to come into the session in a positive frame of mind. Everyone taking part needs to feel a genuine sense of ‘safe space’. A lot of this comes from leaders within the organisation reassuring individuals prior to the test that positive challenge is of benefit to all.

- Building familiarity: It is not advisable for the very first wargame an organisation undertakes to be on a highly sensitive and emotive topic. It often helps to do some practice runs first, either on a generic ‘scenario’ or a low-level issue to build understanding of how the concept works.

- Good facilitation: Management of the session is crucial and this is where the real skill in a wargame comes in to play. Generating sufficient pressure to dig into the issue, but not so much that people crumple; capturing outcomes; encouraging introverts; managing extroverts – these are all challenging aspects which require experienced facilitators.

- Balance of teams: There should be an imbalance between the size of the blue team and the red team. The blue team should ideally be about a third of the size of the red team, to ensure that they feel under pressure and to keep the dialogue short and efficient. An ideal wargame size is 15 red team members to five blue team members and a facilitation team of two to three people.

Facing up to reality

Even using this as a guide, running a wargame is not easy. It takes practice and experience to get it functioning to best effect. Experienced facilitators will smooth many rough edges, until the organisation becomes more familiar with the technique and can start to facilitate sessions independently.

All organisations need to give careful thought to posing a controlled critique of their plans; being unafraid to pose difficult questions. Unless we step back and challenge the status quo, business continuity plans – even the most resilient – will remain vulnerable to damaging blind spots.

Footnotes:

- http://www.strategy-business.com/blog/Leading-in-an-Increasingly-VUCA-World?gko=5b7fc

- These could include managers, employees, local authorities and emergency services, suppliers and providers, senior management, clients, competitors and experts on criminal & terrorism threats or political changes.